In the 2019 parade, Zhang Youxia was seated among vice-national-level Politburo members. (Video screenshot)

[People News] If Zhang Youxia really is, as overseas disclosures claim, brought down together with Liu Zhenli and Zhong Shaojun—and even their entire families are taken away—this would mark the CCP’s top-level power struggle entering an extremely dangerous new phase: shifting from anti-corruption purges targeting “peripheral” generals to directly touching the “core red second generation” and their family networks. The long-maintained intra-party “consensus”—that is, under Xi Jinping’s centralized power framework, red families tacitly acquiesce or at least refrain from open confrontation—would face the risk of complete disintegration.

Over the past decade or more, although Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption storm has swept up many senior military and political officials, it has consistently preserved a “red line” when it comes to the descendants of the founding fathers (especially red second-generation figures within the military). As the son of Zhang Zongxun, Zhang Youxia’s father’s wartime camaraderie with Xi Zhongxun made him a symbolic figure in the military who could, in rare fashion, “stand on equal footing” with Xi Jinping. He is not only a vice chairman of the Central Military Commission, but also a representative of the military’s “old-guard” forces and a bridge for Xi Jinping’s control of the “gun barrel.” After multiple rounds of purges of the Rocket Force and the Equipment Development Department, Zhang Youxia was once regarded as a “survivor” and a “die-hard loyalist.” If he were to be taken down, it would amount to Xi Jinping personally tearing up this red line and sending a signal to the entire red family circle: no one is untouchable, and no one can enjoy immunity.

The consequences of such a rupture would be systemic. Red families are not a monolithic bloc, but they have formed a fragile balance between “protecting the Party” and “protecting family interests.” Once a “full showdown” occurs, potential countervailing forces would quickly coalesce: Liu Yuan, the descendants of Wang Zhen, and the offspring of other founding marshals and generals might shift from passive observation to active joint action. Historically, once intra-party purges in the CCP reach the level of elders, they often trigger chain reactions—the large-scale high-level purges in the late Soviet period under Gorbachev began with touching old Bolshevik families and ultimately led to the collapse of intra-party consensus and an avalanche of the system. Similarly, if the Zhang Youxia incident is substantiated, panic of “everyone fearing for themselves” would emerge within the Party: who can guarantee the next one won’t be themselves? Loyalty within the bureaucratic system would shift from “active allegiance” to “passive slackness” or “covert resistance,” the decision-making chain would fracture, and execution capacity would drop sharply.

Even more deadly is that this disintegration would occur at China’s most fragile moment. With the economy continuing to decline, the population-aging crisis, and the real-estate debt chain stretched taut, turbulence at the top would directly amplify uncertainty. Investor confidence is already fragile; compounded by a vacuum at the military core (Zhang Youxia oversees the CMC’s daily operations, while Liu Zhenli is responsible for combat command), stock markets, foreign-exchange markets, and foreign capital outflows could accelerate. On the social level, rumors have already been fermenting within overseas Chinese communities; if they seep into the mainland (despite the strict firewall), they would further inflame grassroots grievances—the earlier “disappearances” of Qin Gang, Li Shangfu, He Weidong, and others have already left a collective online memory of “the top leadership is in chaos.”

Internationally, Western media would seize the opportunity to hype a “Xi Jinping losing control” narrative, increasing pressure on China in the Sino-U.S. rivalry; allies such as Russia would not, in the short term, waver from the “no-limits partnership” line, but if military-industrial corruption or espionage cases are involved, trust among allies would also be damaged.

In the short term, Xi Jinping still has means to stabilize the situation: convening an expanded CMC meeting, rapidly promoting Fujian–Zhejiang faction or loyal generals to fill the vacuum, or even continuing high-pressure measures under the banner of “larger-scale anti-corruption.” But long-term hidden dangers have already been planted: once the cycle of purges begins, as in Stalin’s late period, bureaucratic inertia intensifies, innovation withers, and regime resilience is continuously consumed. After the Lin Biao incident, the CCP took several years to rebuild order within the military; if a similar crisis were to replay now, and under the dual pressures of the economy and society, the consequences could far exceed those of 1971.

In sum, if Zhang Youxia truly is arrested, it would not be another “victorious anti-corruption” campaign, but rather the death knell of the Party’s “red consensus.” What it portends is not a more stable regime, but a slide from “stable high pressure” toward the abyss of “high-risk loss of control.” China’s future trajectory will depend on the intensity of countermeasures by red families, the timing of Xi Jinping’s restraint, and the degree of awakening of grassroots civic consciousness. At present, everything remains at the rumor stage, but the essence of black-box politics is this: when absence becomes the norm, the truth is often more brutal than rumors.

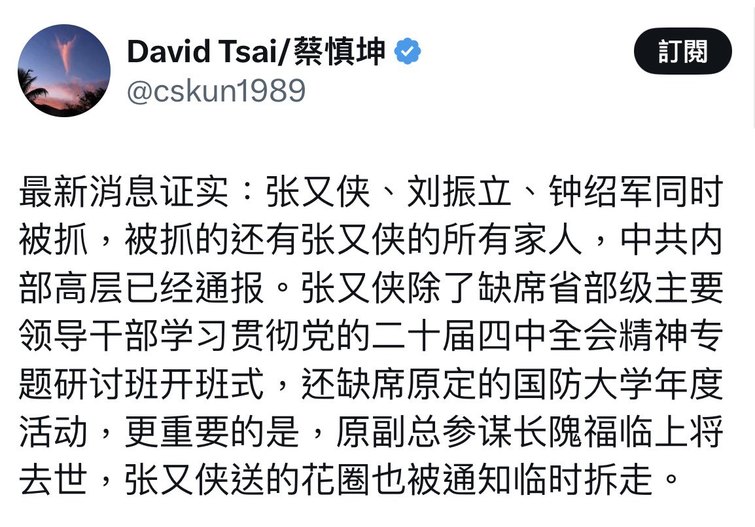

(Source: the author’s X account)

△

News magazine bootstrap themes!

I like this themes, fast loading and look profesional

Thank you Carlos!

You're welcome!

Please support me with give positive rating!

Yes Sure!