The Chinese Refugee Wave in the Xi Jinping Era (People News)

[People News] In the era of Xi Jinping, China’s official media have spared no effort in promoting an image of a “prosperous age”: from the “Chinese Dream” to the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,” from “common prosperity” to “high-quality development.” These political slogans paint the picture of a powerful, confident, and harmonious great nation.

Yet reality stands in stark contrast—more and more Chinese people are choosing to “vote with their feet,” becoming overseas migrants or asylum seekers. Over the past thirteen years (from 2012, when Xi Jinping came to power, to the present), the number of Chinese seeking asylum and emigrating has surged dramatically. This inevitably raises the question: under this so-called “prosperous age,” why are Chinese people flocking in droves to U.S. embassies and consulates in China, petition offices, and major hospitals—these “most crowded places”? This article will compare Xi Jinping’s various political slogans, examine migration data, and analyze the deeper reasons behind this phenomenon.

I. Xi Jinping’s Chinese Dream

Since coming to power, Xi Jinping has rolled out a series of resounding slogans aimed at rallying public support and shaping the national image. In 2012, he proposed the “Chinese Dream,” emphasizing that “realizing the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation is the greatest dream of the Chinese people since modern times,” and promising prosperity through reform and opening up.

In 2013, the Belt and Road Initiative was launched, claiming it would build a “community of shared future for mankind” and propel China to the center of the world stage. In 2014, the “new normal” became a key economic term, stressing a shift from high-speed growth to high-quality development. The report of the 19th Party CongresThe Chinese Refugee Wave in the Xi Jinping Era

s in 2017 declared that “socialism with Chinese characteristics has entered a new era,” outlining a blueprint for becoming “strong.” In 2021, “common prosperity” was elevated to a strategic goal, claiming it would narrow the wealth gap and allow people to share in development outcomes. The 20th Party Congress in 2022 further strengthened “whole-process people’s democracy” and “high-quality development,” while placing “national security” above all else. All of these slogans emphasized a “prosperous age”: economic takeoff, social stability, and people’s happiness. But behind this ornate rhetoric lie economic decline, political tightening, and the accumulation of social contradictions, leading to the public’s disillusionment with the “prosperous age” and a turn toward seeking asylum overseas.

II. The Chinese Refugee Wave in the Xi Jinping Era

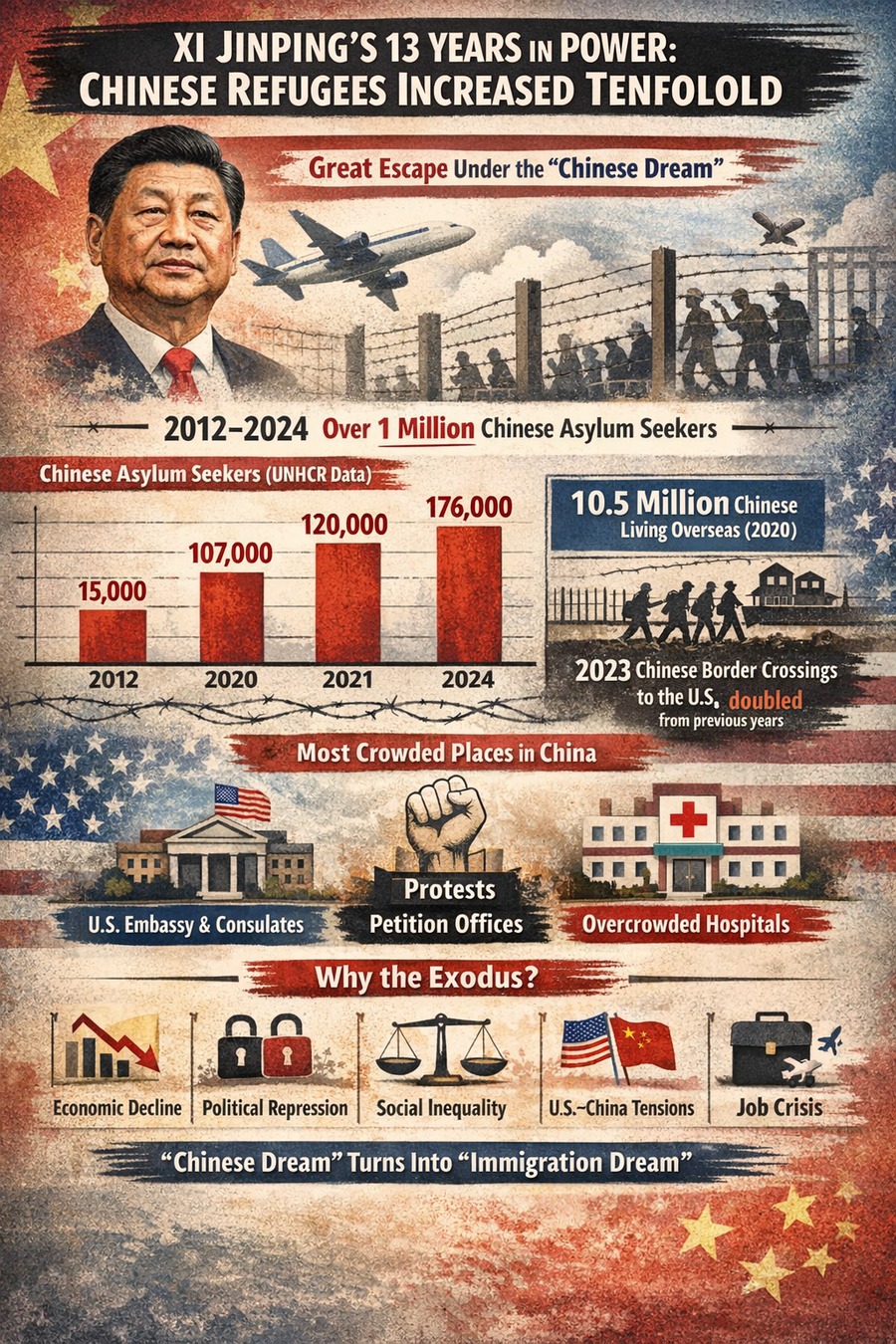

Data show that during the Xi Jinping era, the number of Chinese migrants and asylum seekers has grown explosively. According to statistics from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), in 2012 (the year Xi took office), the number of Chinese seeking asylum overseas was about 12,000 to 15,000. By 2020, this figure had soared to 107,000—an increase of nearly sevenfold. In 2021 it rose to nearly 120,000; by 2024 it had exceeded 176,000.

Overall, from 2012 to 2024, the total number of Chinese people seeking asylum has surpassed one million, breaking the one-million mark. Among destinations, the United States is the top choice: from 2021 to 2024, the number of Chinese illegal immigrants flooding the U.S. border surged, and in 2023 the number of Chinese migrants encountered at the border doubled compared with previous years.

In addition, around 10.5 million Chinese citizens were living overseas in 2020 (as legal new immigrants), a figure that had clearly doubled compared with 2012.

These data form a bitter irony with the “prosperous age” slogans: after the “Chinese Dream” was proposed, the number of people seeking asylum abroad instead jumped from about 15,000 per year to over 170,000? In other words, over the thirteen years of Xi Jinping’s rule, the annual number of Chinese refugees has increased tenfold compared with before Xi took office.

III. China’s Three “Most Crowded Places”

China has three “most crowded places”: U.S. embassies and consulates, petition offices, and hospitals. They vividly reflect the livelihood dilemmas beneath the “prosperous age.” First, U.S. embassies and consulates in China are packed: visa applications and asylum demands have surged, and many people risk their lives crossing borders to seek asylum in the United States, where the asylum approval rate reached 33 percent in 2023. This reflects political repression and economic despair, fueling the rise of “runology” (the study of how to leave China). Second, petition offices are overflowing: petitioners swarm in to complain about land seizures, corruption, and rights violations, only to be suppressed, highlighting the hollowness of “whole-process people’s democracy.” Third, major hospitals are overcrowded: shortages of medical resources, post-pandemic aftereffects, and accelerated aging mean that under “high-quality development,” people still face difficulty seeing doctors and high drug prices. These places are not symbols of “prosperous age” prosperity, but focal points where social contradictions erupt, pushing more people to choose emigration.

IV. Under the “Prosperous Age,” Why Have Chinese Refugees Increased So Sharply?

Why, under a “prosperous age” filled with Xi Jinping’s slogans, have Chinese refugees increased so dramatically?

First, economic factors: despite propaganda about the “new normal” and “high-quality development,” pandemic lockdowns, economic downturns, and persistently high unemployment (youth unemployment once exceeded 30 percent) have shattered middle-class confidence. In 2023, China’s foreign direct investment declined and the real estate sector collapsed, further accelerating the outflow of capital and talent.

Second, political repression: Xi Jinping emphasizes “national security,” tightening control over speech and forcing dissenters into exile. Many asylum seekers cite religious, political, or human rights reasons; since 2012, the total has exceeded one million.

Third, social injustice: under “common prosperity,” the wealth gap has widened, while the burdens of education, healthcare, and elder care remain heavy, pushing families to emigrate.

Fourth, the international environment: amid U.S.–China friction, many view the United States as a “beacon of freedom,” leading to a surge in border migration.

Fifth, China’s employment environment continues to deteriorate; in search of a way out, many people risk near-certain death to leave China, with the aim of working abroad to support their families.

These facts stand in contrast to the slogans: the “Chinese Dream” has become an “immigration dream,” and “great rejuvenation” has been accompanied by a “great escape.”

In sum, the “prosperous age” is nothing more than a propaganda bubble. Migration data and livelihood hardships reveal the true picture. Xi Jinping’s slogans may be grand, but they cannot conceal the public’s despair. If there is no change of regime, this tragic “refugee wave” will continue to play out—and will only intensify.

(Source: the author’s X account)

△

News magazine bootstrap themes!

I like this themes, fast loading and look profesional

Thank you Carlos!

You're welcome!

Please support me with give positive rating!

Yes Sure!