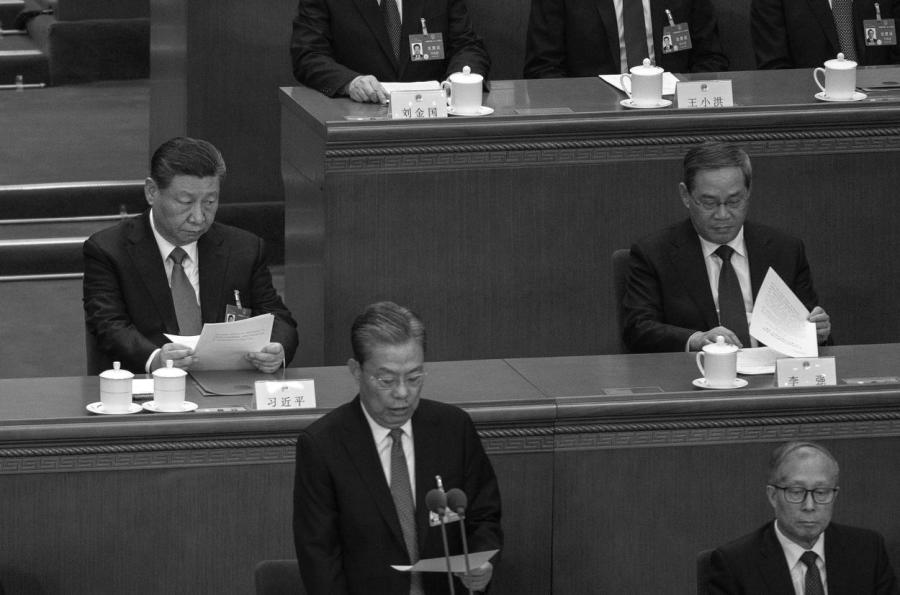

Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping and Premier Li Qiang (right) at the closing meeting of the National People&9;s Congress in the Great Hall of the People. (Photo by Kevin Frayer/Getty Images)

[People News] Just as the outside world expected U.S.-China relations to ease, Beijing suddenly issued six announcements without warning, declaring export controls on rare earth materials and related technologies. U.S. President Donald Trump was furious and immediately announced that starting November 1, the U.S. would impose a 100% tariff on Chinese goods.

Not long ago, Chinese Premier Li Qiang had compared U.S.-China relations to those of a married couple, signaling Beijing’s desire to maintain a stable relationship with Washington. Analysts believe that Xi Jinping’s abrupt policy reversal reveals signs of instability within the Chinese regime.

On October 9, Beijing announced expanded export controls on rare earth-related products. The new rule stipulates that if any product sold by a global company contains Chinese rare earth materials accounting for 0.1% or more of the product’s total value, that product must obtain an export license from China. Industry experts said that it could be extremely difficult for technology companies to prove that the proportion of Chinese materials in their chips, manufacturing equipment, or other components falls below the 0.1% threshold.

On October 10, The Wall Street Journal described China’s latest rare earth export restrictions as “almost unprecedented,” warning that they could disrupt the global economy and give Beijing more leverage in trade negotiations. The move, the report said, could escalate the U.S.-China trade war because it threatens the semiconductor supply chain.

Dmitri Alperovitch, co-founder of the U.S. think tank Silverado Policy Accelerator, said, “This is the economic equivalent of nuclear war — an attempt to destroy the U.S. artificial intelligence industry.” He also noted that this move serves as a “blackmail tactic” ahead of the possible meeting between Trump and Xi Jinping later this month, aimed at pressuring trade talks.

On October 10, Trump criticized Beijing in a post on his social media platform Truth Social, saying that Beijing had sent letters to all countries expressing strong hostility.

Trump said Beijing would impose large-scale export controls on almost everything it manufactures, and even on some products not made in China. He questioned, “This was clearly a premeditated plan,” calling it something “absolutely unprecedented in international trade” and condemning it as a “moral disgrace.”

In response, Trump announced that starting in November, the U.S. will impose 100% tariffs on Chinese products and will also implement export controls on all critical software. He added that if Beijing takes further actions, the timeline for higher tariffs and export restrictions could be moved up.

Regarding Beijing’s latest moves, Trump emphasized that he had not spoken with Xi Jinping. Although the two were scheduled to meet at the APEC summit in South Korea two weeks later, he now believes the meeting is unnecessary.

On September 25, while meeting with U.S. business leaders and scholars in New York, Li Qiang compared U.S.-China relations to a marriage — there may be quarrels, but ultimately both sides need each other. Analysts noted that given China’s economic difficulties, Li’s statement showed that Beijing did not want to worsen relations with Washington. Many also saw his remarks as paving the way for a Trump–Xi meeting. Xi’s sudden hardline turn toward the U.S., therefore, is viewed as a direct slap in Li Qiang’s face.

Overseas democracy activist Wang Dan commented on his online program Wang Dan’s Classroom on September 12, saying that the policy shift from the “marriage analogy” signaling reconciliation to the strict rare earth export controls indicating tension shows that Beijing’s short-term policy reversal is not merely economic retaliation but a product of internal power struggles and external posturing within the CCP.

He added that such drastic swings in foreign policy likely stem from political pressure and power struggles — the first sign of which is instability within Beijing’s ruling circle.△

News magazine bootstrap themes!

I like this themes, fast loading and look profesional

Thank you Carlos!

You're welcome!

Please support me with give positive rating!

Yes Sure!